The Predictable Madness of the Knicks’ Colonel Kurtz

by W. M. | 5 September 2021 | 4-Minute Read

As the Knicks’ distant yet inconveniently relatable Western Conference cousins were battling the Utah Jazz in the second round of the 2021 playoffs, a simple conclusion came to mind, like a diamond bullet through the forehead. The Los Angeles Clippers were not the better team, but they were better coached.

After the Clippers eliminated the number one-seeded Jazz at the Staples Center and reached the Conference Finals for the first time in their rich history of disappointment, Tyronn Lue at last received his elusive flowers. This time around, being a person of color as an NBA head coach was not enough to deny him the credit that he was due. There was no LeBron James (spelled Kawhi Leonard) for Lue’s detractors to take all the attention away from his own merit.

Against a more talented team, and with his best player sidelined with an obscure knee injury, Lue went small by playing Nicolas Batum and Marcus Morris at the five. Quinn Snyder, in spite of his own brilliance, never countered. Rudy Gobert, the All-NBA rim-protector and hegemonic defensive player of the year, was rendered ineffective by having to chase players on the perimeter instead of protecting the rim. He was unable to make the Clippers pay on the other end, for rim-runners are not Dream chasers. Paul George and the small-ball Clips put the Jazz to sleep regardless.

Despite the Clippers’ eventual loss in the Conference Finals, Lue exited the playoffs with his reputation restored as a progressive head coach capable of making sound game-to-game adjustments. He had been bold before, but that narrative seemingly only came out of its shell to reach collective consciousness this past postseason.

In the lesser Conference, the New York Knicks lost to the Atlanta Hawks in the first round of the playoffs. A gentleman’s sweep, spitting and F-words aside. Contrary to the Clippers, their first playoff appearance since 2013 was short-lived. Nevertheless, Tom Thibodeau left the playoffs scene with a similar vote of confidence. He had brought the Knicks back to the playoffs with a roster full of young players, career losers, veteran journeymen and his son-in-law, Elfrid Payton. But Thibodeau didn’t stop there: the Knicks earned homecourt advantage in the first-round.

Unexpectedly, the novelty of excitement replaced the familiarity of dread and Pepe the Frog memes all over Knicks Twitter. Rachel Nichols felt compelled to explain that she had never intended to antagonize Knicks fans, which was met with a perfectly synchronized collective eye roll. Blue and orange jerseys were somewhat cool again. The story was too good for Thibodeau not to run away with the Coach of the Year award, like Scott Brooks, Mike Brown, Byron Scott, and other greats before him.

Entering the 2020-21 season, Thibodeau gave his team a clear defensive identity and a consistent defensive gameplan. The Knicks allowed the eighth-most wide open 3s (17.5 3PA per game) in the regular season yet ranked second in percentage allowed on those shots (34.7%). Some attributed it entirely to luck – the percentages held up for too long not to be in large part about scheme and execution. They also funneled rim attackers to the long arms of Mitchell Robinson and Nerlens Noel, who allowed an NBA-low 58.9 FG% from less than 5-feet. Counterintuitively, their defensive shot chart was working. The Knicks embraced the same defensive identity upon which their success during the Richard Nixon presidency was built and finished the regular season fourth in defensive rating, with no player making either All-NBA defensive team. Offensively, players were given defined roles that highlighted their strengths, with the glaring exception of the starting point guard. Under Thibodeau, Julius Randle became an All-Star, the Most Improved Player and an All-NBA player. A much-improved RJ Barrett made the cover of SLAM magazine, alongside Randle. Against all odds, this crew of overachievers eventually finished the regular season fourth in the East.

It all came crashing, however, in the first round series against Atlanta. After a two-game round of observation at Madison Square Garden, which ended in a 1-1 draw and with a fleeting glimpse of the forthcoming apocalypse on Pennsylvania Plaza, the Hawks wiped out the Knicks. There was no room left for drama in the end, as New York lost games 3, 4 and 5 by a combined 42 points. These men fought with their hearts, but they were outmatched, outplayed, outcoached.

The Knicks struggled to defend the Trae Young-Clint Capela pick-and-roll throughout the series, with their drop coverage looking helpless against Young’s floaters and drives to the basket. Despite the optics, their defense held up, with a 109.7 series defensive rating that would have ranked sixth in the regular season. It is their offense that descended into complete darkness, with a 102.1 offensive rating, which not unlike their series 50.5% true shooting percentage would have ranked last in the regular season.

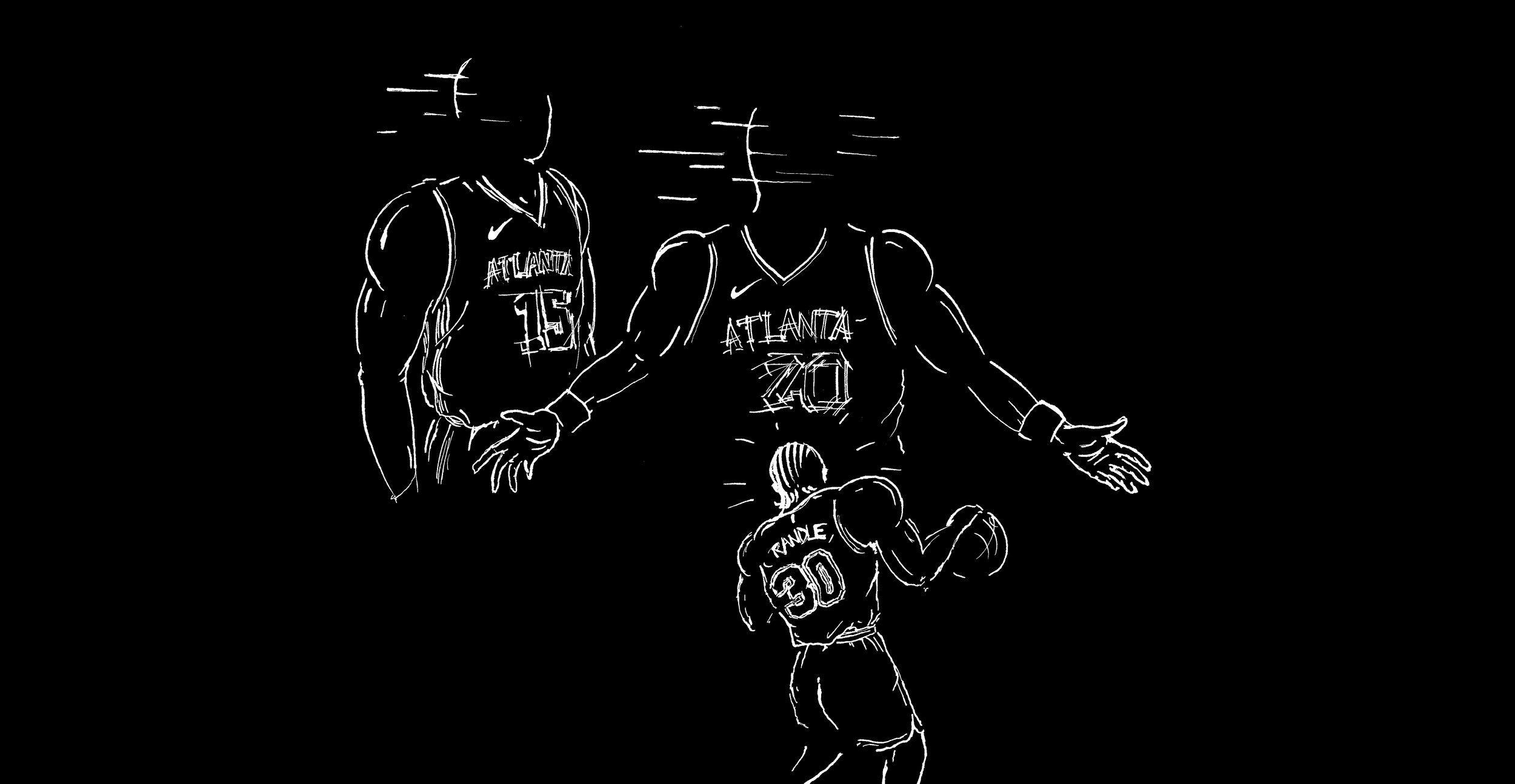

While New York’s roster showed its limitations in the playoffs, perhaps more striking was the lack of adjustments from Thibodeau, aside from starting Derrick Rose in game 3, which didn’t provide the offensive spark that he was hoping for. The problem lied elsewhere – on the opposite end of the positional spectrum. As he did during the regular season, Thibodeau played a rim protector at all times in the playoffs. Nate McMillan dared the Knicks to have Nerlens Noel and Taj Gibson make a play off the catch by having Clint Capela roam as a second line of defense and help in order to block Randle’s path to the rim. The Hawks held the Knicks’ best player in the palm of their hand: Randle averaged 18.0 points per game and ended the series with a 42.5 true shooting percentage and a -12.1 net rating.

Thibodeau had the option to go small with Randle or Obi Toppin at the five to unlock the offense at the expense of rim protection. While the hypothetical success of a small-ball gamble is debatable, Lue succeeded in making this adjustment against Utah by adopting a switch-heavy scheme, which helped lessen the defensive trade-off as it exposed the offensive limitations of a rim-running center. There is always an element of risk in changing strategy in the middle of a series, but maybe one should redefine what consists as risk in the face of imminent defeat. Confronted with the futility of his methods, Thibodeau nevertheless stuck to his original gameplan, however inadequate. By the end of the series, the Knicks had seemingly accepted the inevitability of their fate, with games 3, 4 and 5 having looked like identical carbon copies.

Amidst the glory of Thibodeau’s Coach of the Year announcement, I started wondering why his stubbornness had barely been dissected and why Knicks fans and the NBA media alike were seemingly willing to absolve him of any responsibility for what transpired in the Atlanta series. I thought of the all the years since Mike Woodson's firing, and how low the bar had been set by Thibodeau’s predecessors. Derek Fisher, Jeff Hornacek, Kurt Rambis, David Fizdale, Mike Miller were all characters in a (mostly triangular) masterpiece of dysfunction. None of them ever got another job as an NBA head coach. Throughout their barren 6-year run, Knicks fans had grown used to incompetence. Subconsciously, it became the new standard. Mere competence, by contrast, would look like sheer brilliance. Accordingly, this year’s playoff loss was celebrated. Thibodeau had miraculously taken the Knicks to the playoffs. Knicks fans were freed from mockery. He was freed from accountability.

Before Leon Rose hired Thibodeau to be the head coach of the Knicks, Thibodeau was branded a hard-nosed defensive guru - a general loyal to his soldiers, but devoid of offensive creativity and with little inclination for making game-to-game adjustments in the playoffs. A basketball Republican of sorts. His teams had consistently overachieved in the regular season – with him squeezing every ounce of talent from his players – but had seldom found the same level of success in the postseason. His stubbornness was legendary – almost endearing from a distance. It also cost his teams in the playoffs as his resistance to change made them more predictable in a 7-game series. Despite fairly successful stints in Chicago and Minnesota, Thibodeau’s winning percentage has dropped by a strikingly wide margin from the regular season (58.7%) to the postseason (41.0%).

Thibodeau was also known for his primordial instinct for 2-point field goals and his aversion for volume 3-point shooting. Predictably, the 2020-21 Knicks only attempted 29.9 3FGA per game during the regular season, fourth lowest in the league, despite having the second highest 3P% in the Association at 39.2%. Inversely, the Knicks attempted the eighth-most 2FGA per game with the second worst 2P% percentage among all 30 teams at 49.0%. While an increase in 3P volume could lead to a decrease in shot quality – thus 3P% – there is nonetheless irony to be found in this picture. The Knicks only shot 58.0% from less than 5 feet in 2020-21, second worst in the league. Considering the team’s inefficiency at the rim, particularly from its cornerstones Randle and Barrett, it is difficult to envision the Knicks running a dynamic offense if they don’t attempt more 3s. Unfortunately, no Thibodeau-led team has ever ended a season in the top-half in 3s attempted per game:

2010-11 Bulls: #17 (17.3 3FGA)

2011-12 Bulls: #18 (16.9 3FGA)

2012-13 Bulls: #29 (15.4 3FGA)

2013-14 Bulls: #28 (17.8 3FGA)

2014-15 Bulls: #16 (22.3 3FGA)

2016-17 Timberwolves: #30 (21.0 3FGA)

2017-18 Timberwolves: #30 (22.5 3FGA)

2018-19 Timberwolves: #23 (28.5 3FGA) *40 games

2020-21 Knicks: #27 (29.9 3FGA)

Unavoidably, the modern game is built around shots at the rim and 3-point shots – with the midrange game mostly a valuable bail-out option this side of Kevin Durant and Kawhi Leonard. With no volume 3-point shooting to make up for their lack of efficiency at the rim, the Knicks tied their fate to a heavy dose of midrange shots. While one can appreciate Thibodeau’s emphasis on the quality of 3s taken, the dichotomic assumption that shot quality should come at the expense of volume seems misguided, if not conveniently simplistic. The Knicks have been behind the curve since 2013-14 in terms of shot selection, and they don’t appear to be much more progressive under Thibodeau. His first season in New York is not a revelation or merely the fruit of coincidence – it is consistent with his entire coaching career.

The Knicks’ relative success last season has understandably overshadowed question marks about the ceiling of a Thibodeau-coached team. With the standards of this franchise having continually reached new lows since 2013, questioning Thibodeau’s coaching after this past season feels somewhat unnecessary. Ungrateful even. Admittedly, he has infused the franchise with a sense of competence and confidence that had completely vacated Madison Square Garden. However, Thibodeau’s style of basketball could be the roadblock to another banner or mere playoff success should his approach remain this conservative in the coming seasons. There are levels to this, with each playoff round requiring tougher adjustments and reducing space for inefficiency. Tyronn Lue didn’t meekly respond to the challenges posed by the Utah Jazz – he aggressively answered them. For Thibodeau to be immortalized in New York, he will need to show the same level of flexibility at some point, for the NBA is not a temple for mad old men anymore.